… for Visual Effects

Tip #502: The Challenges of Changing a Color

Larry Jordan – LarryJordan.com

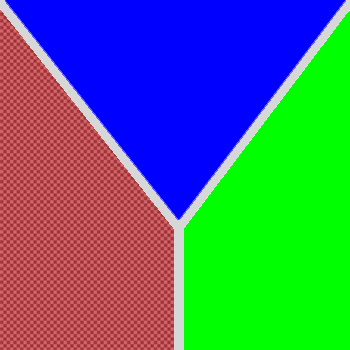

Gray-scale values provide texture.

This is Brittney. She’s one of the models from the now-defunct GlamourKey.com website. She’s wearing a deep blue shirt. Except, the script called for her to wear burgundy. Or maybe light pink, it was a toss-up…

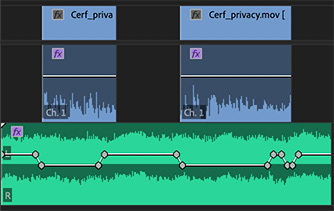

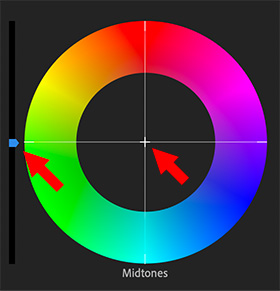

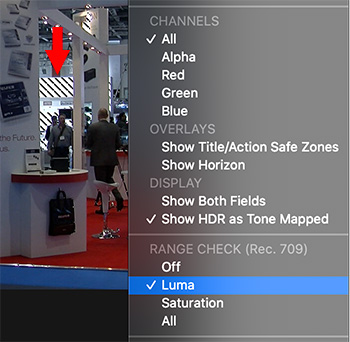

The problem is that when we are changing the color of something in post, we can change it’s hue or saturation, but we can’t change it’s gray-scale. Why? Because variations in gray-scale provide objects their texture. If I replace both color and gray-scale her shirt, which has nice folds in the sleeves, suddenly become a block of solid, undistinguished color.

NOTE: To prove the point about texture, the background behind Brittney on the left has a single gray-scale value: 50%. The background behind her on the right, has gray-scale values that range from 0 to 100.

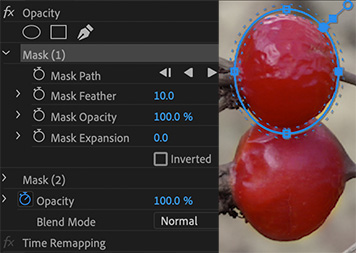

So, in Brittney’s case, I can replace dark blue with dark green, or dark red, but not light pink, because I can’t change the gray-scale values enough in her shirt to create light pink from burgundy.