… for Codecs & Media

Tip #865: What is HDMI?

Larry Jordan – LarryJordan.com

HDMI is an uncompressed audio and video standard for connecting devices.

We’ve used it for years, but what, exactly, is HDMI? At its simplest, HDMI is a standard used to connect high-definition video devices.

More specifically, HDMI (High-Definition Multimedia Interface) is a proprietary audio/video interface for transmitting uncompressed video data and compressed or uncompressed digital audio data from an HDMI-compliant source device, such as a display controller, to a compatible computer monitor, video projector, digital television, or digital audio device. HDMI is a digital replacement for analog video standards.

NOTE: See the use of “uncompressed” in the preceeding paragraph. HDMI may be easy to use, but it provides the highest possible quality.

Several versions of HDMI have been developed and deployed since the initial release of the technology in 2003, but all use the same cable and connector. In addition to improved audio and video capacity, performance, resolution and color spaces, newer versions have optional advanced features such as 3D, Ethernet data connection, and CEC extensions.

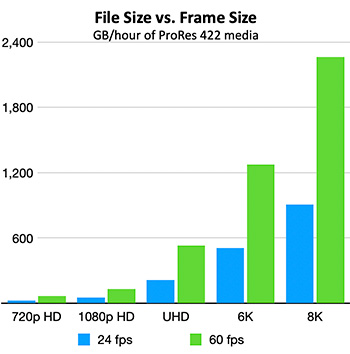

The challenge remains for HDMI to keep up with the constant growth in media technology, specifically larger frame sizes and faster frame rates.

As you’ll read in Tip #863, the latest version of HDMI seeks to take our computers and TVs “to infinity … and beyond.”

Here’s a Wikipedia article to learn more.